For 47 years, Arrow used heroin, cocaine, and another illicit drug several times a week. Then, on Oct. 17, 2018, he stopped.

The 61-year-old Miami resident says he got tired of “constantly losing everything I had, feeling sick all the time, and defecating in the street.” And one excruciating day, his partner died in his arms from drug use.

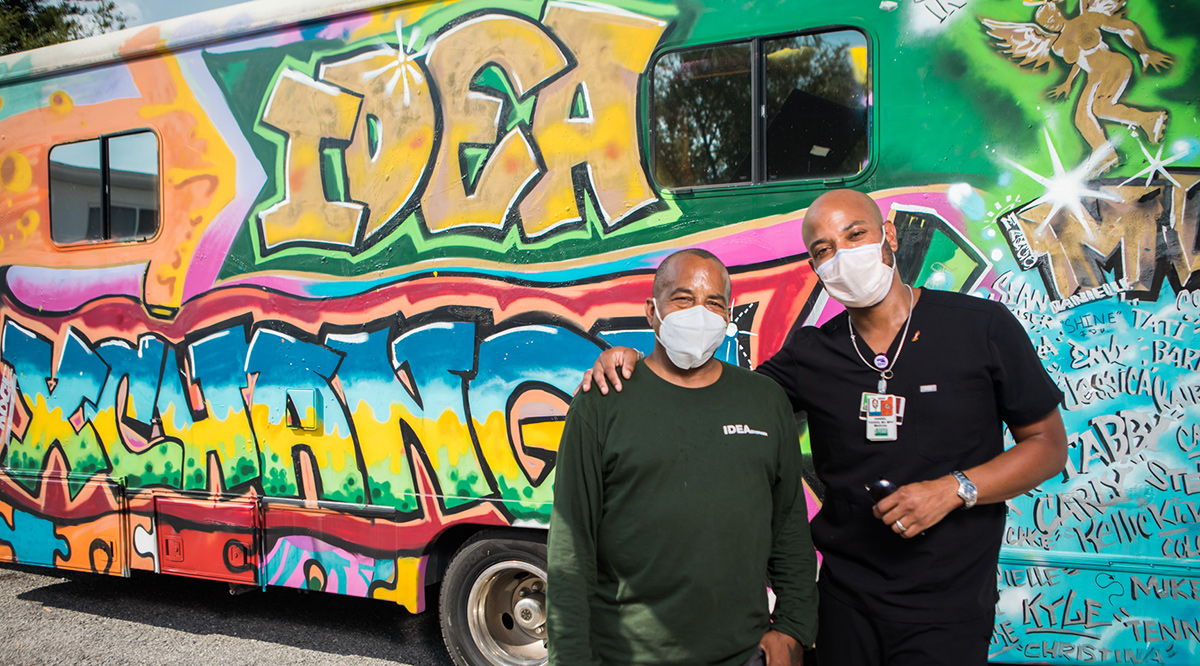

But Arrow says he couldn’t turn his life around on his own. Asked how he did it, he answers simply: Dr. Tookes.

Hansel Tookes, MD, MPH, an associate professor at the University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, is the physician behind a leading harm reduction program that serves 1,800 people who use drugs.

Tookes — like a growing number of providers who use the somewhat controversial harm reduction approach — opts not to push people to abstain from illegal drug use. Instead, he and others focus on helping people minimize such dangers of drug use as overdoses and infectious diseases by providing supports like sterile syringes, the overdose-reversing medication naloxone, and even street-based health care.

In a victory for the approach, New York City recently authorized two overdose prevention centers — sites that provide hygienic spaces for illicit drug use and professional help in case of overdose — that are the first such officially sanctioned centers in the United States.

Even the Biden administration is backing harm reduction. In December, it announced $30 million in funding for syringe services programs (SSPs) and similar measures.

“There is so much we can do to decrease the risk of infection, illness, and death. People should not have to stop using for us to start helping.”

Jessie Gaeta, MD

Addiction specialist and assistant professor at Boston University School of Medicine

The increased interest in harm reduction comes in the wake of the highest rates of U.S. overdose deaths ever recorded: more than 100,000 in the 12-month period ending in April 2021, according to the most recent data. Fueled in part by pandemic-related stresses, that represents a 30% jump over the prior 12-month period.

Not everyone is on board. Some jurisdictions are moving to limit harm reduction services, driven by a concern that they promote drug use. But supporters point to research suggesting otherwise. For example, people who use SSPs are three times more likely to reduce or stop drug use than those who don’t, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Whether or not harm reduction leads to stopping drug use, proponents argue that aiding individuals who use drugs remains a moral imperative.

“There is so much we can do to decrease the risk of infection, illness, and death,” says Jessie Gaeta, MD, an addiction specialist and assistant professor at Boston University School of Medicine. “People should not have to stop using for us to start helping.”

Clean needles, tourniquets, and more

Six days a week, staff from the Miller School of Medicine program search Miami’s streets, underpasses, and alleyways looking for people who use illicit drugs. Among other goals, they hope to swap used syringes that can spread HIV, hepatitis C, skin infections, and other serious conditions for clean ones.

The effort — the IDEA (Infectious Disease Elimination Act) Exchange — launched in 2016 after receiving special legislative approval to pilot Florida’s first legal SSP. Since then, the program has distributed more than 1 million clean syringes, and its success has led to SSPs statewide.

Today, distributing clean syringes is more vital than ever, experts say. That’s because the effects of the synthetic drug fentanyl — which now dominates the opioid supply in several areas — fizzle out faster than those of other opioids.

“To avoid withdrawal, users need to inject twice as often, typically six to 10 times a day, greatly increasing their risk,” says Gaeta, who serves as chief medical officer of Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

Each month, Gaeta’s team works with a local SSP called Access, Harm Reduction, Overdose Prevention, and Education (AHOPE) to distribute thousands of sterile syringes — as well as tourniquets and other drug paraphernalia — through four mobile clinics. Created by the Kraft Center for Community Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in 2018, the mobile team — Community Care in Reach — uses real-time city data to identify Boston’s overdose hotspots.

Along with the syringe exchanges, staff members offer instruction in avoiding riskier drug use behaviors.

“People might prepare drugs with any water they have access to — sometimes puddle water or toilet water — and we suggest single-use sterile water, which we distribute, or at least tap water,” explains Gaeta. “There are several steps in the injection process where people can reduce their risks.”

It’s not always easy to get such lessons going, she adds. They require building trust first.

“I remember one woman in an encampment under a bridge. For weeks, all I saw were a few strands of her hair popping out of her sleeping bag. At first, we would just leave supplies like sandwiches and safer injection kits.”

Eventually, the two connected, and Gaeta was able to provide wound care, screening for sexually transmitted illnesses, antibiotics, and naloxone. “She was even willing to try medication for opioid use disorder and has had longer periods of not injecting. And she connected me to a larger network so I could help even more people,” she says.

Tookes is grateful that students and residents get to witness such experiences through his program. “It really gives me hope that the next generation of health care providers are learning to treat people who use drugs with the dignity they deserve,” he says.

Doctors on the move

People who inject drugs account for about 1 in 15 HIV diagnoses in the United States, and the majority of those diagnosed with hepatitis C. To address these and other health concerns, providers focused on harm reduction head out to offer care in hard-hit neighborhoods.

“Our medical center is just a few subway stops from some of the poorest neighborhoods in the country. But it’s exceptionally difficult to get people who use drugs into the larger health care system” because of issues like fear of stigma, says Brianna Norton, DO, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at the Montefiore Health System and Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

Two years ago, Norton helped launch a local clinic to treat infectious diseases, opioid use disorder, and other conditions among people who use drugs. The clinic is housed within a nonprofit agency — New York Harm Reduction Educators (NYHRE) — that provides a syringe services program.

Now, NYHRE is also home to one of the city’s first overdose prevention centers. And though Montefiore-Einstein does not run that service, it does treat patients who use it.

“We cannot treat someone for their opioid use disorder if they’re not alive.”

Brianna Norton, DO, MPH

Infectious disease specialist at Montefiore-Einstein

“It’s wonderful if someone wants to access a safe way to use drugs, and then if they need health care, they can get it under the same roof,” says Norton. She adds simply: “We cannot treat someone for their opioid use disorder if they’re not alive.”

In Boston, the Mass General program takes health care on the road in a custom-built motor home equipped with a full-sized exam table, waiting area, and wheelchair lift. There, patients receive immunizations, injection site wound care, and addiction treatment, as well as housing referrals, clothing donations, and other services.

Meanwhile, during the pandemic, Miami’s IDEA took its outreach program even further, providing “tele-harm reduction” — an array of services from prescription medication to mental health care delivered via remote providers and outreach staff with iPads. In a 2021 study, the effort successfully reduced the HIV viral load of 78% of program participants to undetectable levels.

Tookes attributes the success largely to his team’s commitment. “They ask what help a person needs to take their medication,” he says. “They will deliver medications to patients’ homes or tents. They will go look for patients when they can’t find them.”

Reversing deadly overdoses

Even if people who use opioids stay relatively healthy, they still face the risk of overdosing. That’s why distributing the reversal medication, naloxone, is a mainstay of harm reduction efforts.

Often, naloxone is simply distributed together with clean syringes. But emergency departments (EDs) offer another crucial distribution opportunity, say experts.

Consider some recent data: More than half of fatal overdoses occurred within three months of an ED visit, according to one study. Yet less than 8% of ED overdose patients receive a naloxone prescription.

In 2021, Banner - University Medical Center Phoenix’s ED became the first in Arizona to offer patients naloxone. Doing so was no simple matter.

First, there were technical state and hospital-related rules about "distributing" versus "dispensing" naloxone, which were eventually resolved by providing prepackaged doses of medication. Then there was the work necessary to reassure staff that they weren’t breaking any of those rules. And there also was a need to convince some patients and families that naloxone wasn’t risky.

“Sometimes people are nervous to have naloxone in their home, but it’s safe, and it can be crucial in saving someone’s life,” says Daniel Brooks, MD, a Banner medical toxicologist.

So far, some 200 people have received naloxone kits in a Banner ED. They also went home with the number for Banner’s Opioid Assistance and Referral line (888-688-4222) — a 24/7 information center staffed by nurses and pharmacists trained to help with naloxone and anything else related to opioid use issues.

“Sometimes people are nervous to have naloxone in their home, but it’s safe, and it can be crucial in saving someone’s life.”

Daniel Brooks, MD

Medical toxicologist at Banner Health

In Baltimore, MedStar Health distributes naloxone in its EDs and simultaneously matches overdose patients with an Opioid Survivor Outreach Program recovery coach. These three specially trained staff members connect patients with harm reduction supports, opioid use disorder treatment, and other services.

But perhaps above all, they provide personal support.

“I can meet people in their most vulnerable time of need,” notes one of the coaches, Joshua Shetterly. He then can follow up for months, meeting people in their homes or on the street.

Shetterly, who lost his brother to an overdose, loves the work. “If I can help prevent just one family from experiencing what my family experienced from the loss of my brother, then I’ve done my job,” he says.

An attitude shift

Whatever the drug-related service, harm reduction experts say the approach relies on one crucial tool: respect.

“We cannot be telling people they have to change in order to get support,” says Susan Collins, PhD, co-director of the Harm Reduction Research and Treatment Center at the University of Washington (UW) School of Medicine in Seattle.

UW’s program, run out of Harborview Medical Center, was created with significant input from people who use drugs. In it, patients identify their own harm reduction and quality-of-life goals. Then, counselors check in regularly to help participants track progress and change behaviors.

And though abstaining is not always a goal, about half of her Harborview patients eventually stopped using, says Collins. Often, people are able to quit because they are no longer “immersed in shame or feelings of failure about their drug use.”

In New York City, the Mount Sinai Hospital’s Respectful and Equitable Access to Comprehensive Healthcare (REACH) program weaves nonstigmatizing harm reduction support into mainstream health care.

“People who are actively using drugs are welcomed in the same waiting room as our other primary care patients and have access to exactly the same services, including specialists,” notes REACH director Jeffrey Weiss, PhD. “These are individuals who so often have felt poorly treated, judged, and marginalized by health care professionals.” He says REACH manages to attract such patients partly because of its close connections with trusted community organizations. “What we’re doing is something really new in medicine, and we would love to see it expand.”

For Collins, harm reduction is about nonjudgmentally meeting patients where they are in their journey. “I am here no matter where you're at,” she says. “No matter how difficult things get, I will always care for you.”