Editor’s note: Academic medicine has been challenged in recent years by workforce shortages, a pandemic, and increasing public anger and distrust toward health care workers, leading to unprecedented levels of burnout and attrition. In this series, AAMCNews speaks with physicians and trainees to share stories of why they stay in medicine despite these challenges.

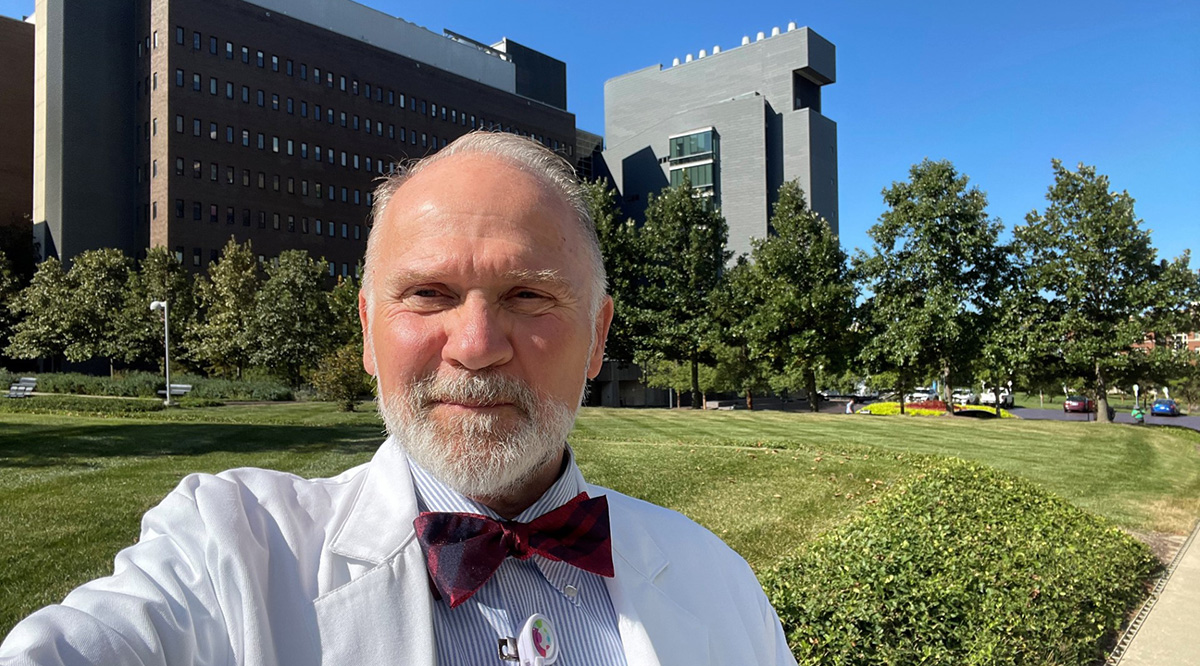

Donald Batisky, MD, FAAP

Associate Dean, Medical Student Admissions and Special Programs

Professor of Pediatrics

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Pediatric Nephrologist, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Cincinnati, Ohio

Donald Batisky, MD, had recently settled into his new role as an associate dean at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and as a practicing pediatric nephrologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center when he got a surprising message from a colleague about a patient who recognized the name Batisky. This patient had seen the announcement that Batisky was returning to Ohio, the state in which Batisky was raised, went to college and medical school, and started his medical practice more than 30 years before. This patient (now an adult) told her doctor that Batisky had been her first pediatric nephrologist 14 years earlier at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus when Batisky was practicing there. Batisky remembered her well. The patient had come into his care as a newborn with a genetic kidney disorder that leads to progressive loss of kidney function resulting in the need for eventual kidney transplantation. Over the roughly four years that Batisky treated her, she was followed closely for changes in kidney function and high blood pressure. Batisky was touched that, all these years later, the patient had remembered him and asked about him.

Batisky decided to pop in on one of her transplant clinic appointments and was amazed at the instant mutual recognition. She gave Batisky a big hug, and he was delighted to hear about how she had overcome further health challenges in young adulthood and was now living a full life as a transplant recipient. In fact, at that visit, she introduced Batisky to her fiancé.

For Batisky, seeing the difference he made in this young woman’s life was incredibly rewarding. But Batisky has rarely ever doubted that medicine — and academic medicine, in particular — is his calling. As a child, he recalls accompanying his grandmother to the doctor’s office for her diabetes treatments and deciding then and there that he wanted to be a healer. As a first-generation college student, Batisky sought out volunteer opportunities in health care and found encouragement in physician mentors who guided him, eventually, to his passion for pediatric nephrology. Though the profession has come with challenges, such as the exhaustion of long shifts and the pain of losing patients, for Batisky, the rewards have been worth it.

In addition to patient care, Batisky has found meaning and harmony through his work as a professor, mentor, and now, as an admissions dean, training and supporting the next generation of physicians. The gravity of these roles hit home in the spring of 2020, when he watched several cohorts of medical students and residents he was mentoring at Emory University College of Medicine face the uncertainty, stress, and grief that came with entering the profession during a time of crisis. As COVID-19 spread, Match Day celebrations and any kind of nonclinical meetings were made virtual. In-person clinical instruction was continued with extreme caution, including full PPE, social distancing, and other measures that made bonding with the students a challenge.

“It was so surreal,” he recalls. “It was a very different way to teach hands-on clinical medicine. But yet, we did it.”

Shortly after seeing his 2020 class of mentees graduate to residency, Batisky welcomed the medical school class of 2024, the first to start their medical school experience during the pandemic. That fall, most of his advising meetings were held over video chat, and even their White Coat Ceremony took place quasi-virtually. The ceremony was filmed for a remote audience and mentors and students were masked and socially distanced. As this was the first occasion his group was in the same place, Batisky marked the moment with a selfie, with the students posing, masked and socially distanced, in the background. Most of those students are now completing their final year at Emory University College of Medicine, and although Batisky moved back to Ohio last year, he did so under the condition that he would continue to serve as the advisor for the 2024 class until their graduation. The socially distanced photo hangs, framed, in his office in Cincinnati as a reminder of that harrowing — but also inspiring — time in his life and career.

Now, as the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center is, again, requiring its health care workers to wear masks due to an uptick in COVID-19 infections, Batisky reflects on the trials and lessons from the pandemic.

“I'm realizing life is always full of change and the need to be adaptable,” he says. “And it does show you the grit and resilience and durability of the human spirit in a way.”

To share your story of why you stay in medicine, fill out this form.