Drinking the blood of a rosy-cheeked adolescent. Munching on a paste of dried human remains. Spending hours submerged inside a greasy, decomposing whale. People around the world have been submitting themselves to sometimes odious and often creepy medical treatments from time immemorial.

But while such bygone behaviors may seem gullible or grotesque to modern sensibilities, a dose of humility may be in order. Today, we have sophisticated, evidence-based systems for assessing medical theories and treatments. Before that, how best to treat various conditions was pretty much anyone’s guess.

For centuries, determined healers simply applied the reasoning that fit the world as they saw it. For example, getting a patient to generate massive amounts of sweat, vomit, or feces was considered a sign of success because of the belief that those symptoms helped expel disease from the body. Back then, as sometimes now, patients generally accepted conventional medical wisdom without asking too many questions.

Why, then, do we seem to get a kick out of the nasty habits and wacky notions of past generations?

“Humans are a very curious species. It’s part of our nature to be attracted to things that are somewhat strange,” says Lydia Kang, MD, author of Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything. “Sometimes that gets us into trouble, but it also speaks to our desire to get answers to important questions.”

“I hope we maintain that curiosity,” adds Kang, an associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. “There’s no better way to keep advancing than to continue exploring, correcting course, and learning.”

Here are six fairly icky, somewhat bone-chilling, and yet entertaining treatments from the past that show how far people were (and sometimes still are) willing to go to protect their health and prolong their lives.

Milk of human kindness?: Dairy-based transfusions

In 1854, two Canadian doctors had a cow delivered to their hospital. Drs. Edwin Hodder and James Bovell did not plan to provide patients with fresh dairy products. Instead, they aimed to inject milk as a substitute for blood.

To them, the underlying science was straightforward: The “oily and fatty particles found in milk were convertible into the white corpuscles of the blood.”

The first milk transfusion recipient, a cholera patient, did quite well, but others passed away. Still, the approach began gaining traction in the United States, and one adherent declared that “Intravenous Lacteal Injection [would have] a brilliant and useful future.”

But as deaths rose, so did skepticism.

One creative New York doctor, Joseph Howe, MD, conjectured that using human milk made more sense. In one such transfusion, though, Howe witnessed a dire reaction, including a dangerously low pulse. “The effect of the milk was so [clear] that all present to the operation expected a fatal termination, but were happily disappointed,” he wrote in 1880.

Not long after this and similar failed attempts, physicians began rejecting the milk-based approach. In the coming decades, scientists began to unravel the mysteries of human blood. Thankfully, they also figured out who made an appropriate donor as well as how to safely transport and transfuse the life-giving fluid.

A calming killer: Morphine for teething

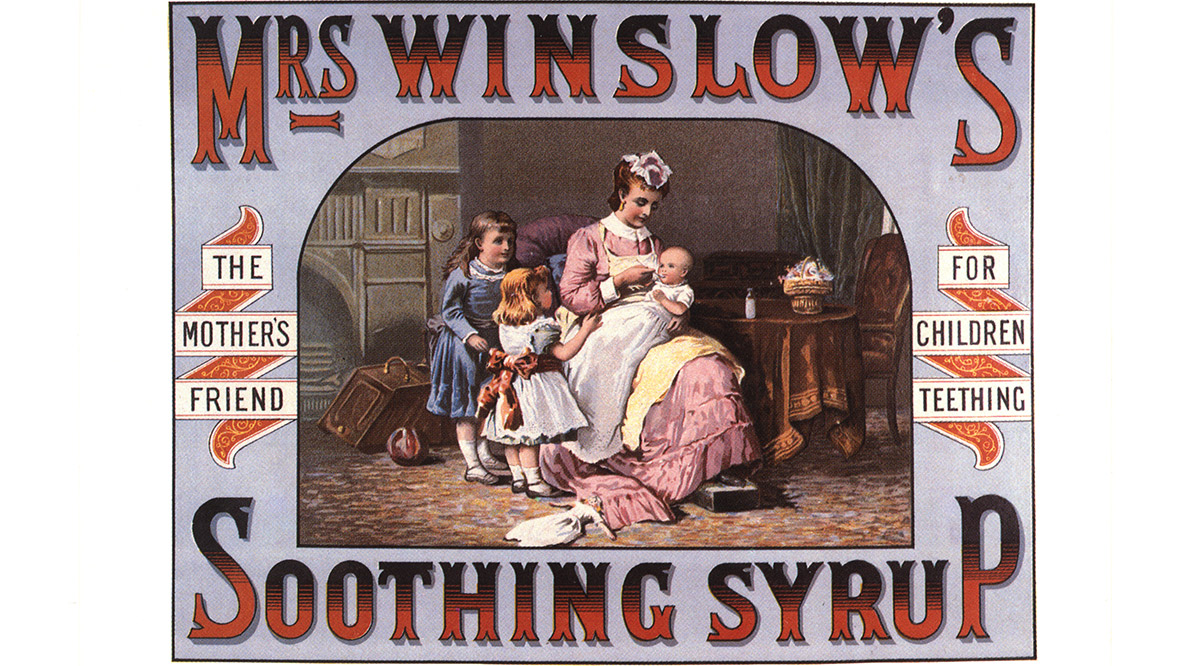

Mrs. Winslow was hailed as an “untiringly devoted” healer of children and the creator of a pediatric cure that “operates like magic.”

What she — or her company — really did was distribute morphine and alcohol to huge numbers of cranky and uncomfortable children across the United States.

Created in 1849, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup claimed to calm young children, soothe their teething pain, relieve their constipation, clean their teeth, and more. By 1868, the company was shipping some 1.5 million bottles annually.

Testing showed that one teaspoon of the 25-cent liquid delivered the equivalent of 10 times the then-recommended maximum amount of morphine for youngsters. And the company advised dishing out that amount three or four times daily.

But instead of easing children into a sweet night’s rest, experts believe it sent thousands to their deaths. Yet, because many parents did not link the fatalities to the syrup, it remained popular for decades.

Finally, in 1906, the U.S. Pure Food and Drug Act required that labels identify ingredients and criminalized selling “adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs or medicines.” Thus began the demise of Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup — it lingered in an altered form for a while — as well as the birth of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

A whale of a cure: Blubber for rheumatism

Rheumatism is so uncomfortable — the condition causes swelling, joint inflammation, and loss of motion — that it’s understandable people might go to any lengths to treat it.

And in the late 1800s, in Australia, some certainly did. Many desperate patients climbed into a hole carved into the carcass of a whale that had been brought ashore for this rather distasteful treatment.

Patients were told to remain inside the carcass for 20 or 30 hours, with occasional breaks, and relief was said to last up to 12 months.

What was the thinking behind the blubber-based approach? The heat and gases emitted by the decomposing carcass were believed to create a rich sweat box of healing compounds. As for the treatment’s origin, some reports point to a drunken man who stumbled into a whale carcass and later emerged free from rheumatism.

After newspaper reports publicized the carcass treatment, it spread to the United States and Europe. The treatment’s popularity ensued in spite of its notable stench. “Great blasts of gas and horrible bubbles would gush out around us,” one patient wrote. “Everyone I met [afterwards] shied at me — a leper could not have been avoided more.”

As the whaling industry began to decline, so did the goopy therapy. Today, medical providers have numerous rheumatism treatments at their disposal, all of which are far less exotic — and malodorous — than the whale cure.

Blowing smoke: Tobacco enemas

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans were quite infatuated with tobacco and even hailed it as a treatment for more than 50 health conditions. Administering it as an enema was, then, perhaps not an entirely bizarre next step.

In England, the approach grabbed great attention as a potential way to resuscitate Londoners who had stumbled into the River Thames.

One of the first such recorded uses took place in 1746. After a man’s wife was pulled from the water, The Lancet explains, “amid much conflicting advice, a passing sailor proffered his pipe and instructed the husband to insert the stem … and blow hard.”

The woman seemed to have quickly regained consciousness — though perhaps simply from the shock of having a fire placed beneath her bottom.

A specific medical theory underpinned this bizarre practice: The tobacco would stimulate respiration, and the smoke would warm and dry the patient’s insides.

Special devices created to perform the procedure included both a chamber to burn the tobacco and tubes to blow the smoke into the rectum.

The approach became so popular in the 18th century that a humane society placed resuscitation kits along the river and promised to pay the impressive sum of four guineas to anyone who rescued a drowning victim.

After physicians realized that using one’s mouth to deliver the enema could be disastrous — one could accidentally swallow some germ-ridden stool, for example — they replaced that method with a bellows-based one.

Soon, tobacco enemas gained popularity in treating other health problems, from headaches and hernias to stomach cramps and cholera.

The popularity of the practice began to wane in the 1800s after British physician Benjamin Brodie started publicizing tobacco’s negative effects. As for drowning victims — or anyone else who has stopped breathing — two U.S. physicians proved in 1956 that mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was a much more effective approach to saving lives.

Dining on flesh and blood: The cannibalism cure

Sipping human blood, smearing human fat, munching on dried flesh — these are not the rituals of some grisly cult but common behaviors practiced for centuries in the hopes of achieving good health.

The approach made perfect sense to many respected thinkers, including Leonardo da Vinci. The great polymath believed that, “In a dead thing insensate life remains which, when it is reunited with the stomachs of the living, regains sensitive and intellectual life.”

As far back as ancient Rome, patients drank the blood of slain gladiators to bolster their strength. Medical vampirism was practiced during the Renaissance as well, with one notable practitioner suggesting that the elderly could regain their vigor by sucking from the vein of a “willing, healthy, happy” teenager.

Eating human flesh was also deemed medicinal for centuries. Consider this 17th-century German cure: a dried jerky of wine, myrrh, aloe, and chopped-up corpses.

But perhaps the most popular type of human-sourced potions involved mummified remains. Often ground into a fine powder, the potion was used as a painkiller, cough suppressant, and blood thinner. In time, the practice became so popular that a thriving fake-mummy trade arose, with the potions actually derived from recently executed criminals and other dubious sources.

Medical cannibalism finally began to die out in the 18th century, but the use of human body parts continues today in the form of life-saving organ donations, the first of which was successfully completed in 1954 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Traditional treatment or slimy scam?: Snake oil

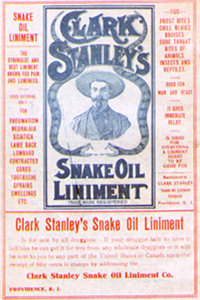

For centuries, oil from water snakes has been used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat inflammation, arthritis, and other joint conditions. It’s charlatans who gave snake oil its bad name.

A bit of history explains how that happened.

Chinese laborers headed for the Transcontinental Railroad in the mid-1800s are thought to have brought snake oil with them to America. These new arrivals likely shared the treatment with others doing backbreaking work beside them.

There were, however, no Chinese water snakes within miles, so determined salesmen began using rattlesnakes instead. Unfortunately, the rattlesnake concoction was not nearly as effective as the Chinese snake oil.

But rattlesnakes did contribute panache. In 1893, entrepreneur Clark Stanley took the stage at the Chicago World’s Fair and sliced open a live rattler, dazzling onlookers. Other salesmen soon launched elaborate “medicine shows” to promote their cure-alls, most of which ended with the dramatic healing of a shill from the audience.

The deception went even further, though: The treatments often contained not a single ounce of snake oil. In fact, a 1917 assessment of Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment found that it contained such ingredients as red pepper, turpentine, and just a dab of fatty oil (probably from cows).

Although Stanley and his ilk were fakes, modern-day research suggests that Chinese water snake oil may have real health benefits — as an anti-inflammatory and blood thinner, for example — stemming from high levels of omega-3 fatty acids.