In Greek mythology, Apollo was the god of disease and healing. He also ruled over the domains of music and poetry.

In ancient Egypt, physicians served as scribes and artists, capturing medical procedures on papyrus in hieroglyphics. And during the 15th century, artists seeking creative materials and physicians seeking cures mingled at apothecary shops and began productive collaborations.

Clearly, the interweaving of art and medicine has a long and rich history.

Although some may see the worlds of arts and medicine as distinct — one squishy and subjective, the other more scientific and objective — doctors have for generations appreciated how artistic pursuits can enhance their medical skills.

From a New Yorker cartoonist-medical educator to a photographer-radiologist, the physicians profiled here share their thoughts on how merging art with medicine helps them treat patients, enhances communication, and soothes their spirits in times of stress.

Seeing more clearly: A photographer-radiologist

Carolyn Meltzer, MD, admits she’s a bit obsessed with the visual world.

Meltzer has had a camera in her hands since childhood, and the dean of the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California has shown her photographs — often stark black-and-white nature scenes — in more than 50 exhibitions in the United States and Europe.

Meltzer has also spent her career studying PET scans and other diagnostic images to better understand the brain and conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“What drew me to the imaging sciences was my desire to use pictures to help solve problems,” says Meltzer, who is also a Keck professor of radiology.

For decades, though, Meltzer opted to keep her photographic pursuits separate from her medical career.

“I came up in medicine at a time when you had to be all in. We didn’t yet understand that doctors need multiple aspects to their lives,” she says. “I’m much more comfortable talking about my photos now.”

In fact, Meltzer is confident that taking photographs enhances her clinical skills.

Creating a photograph requires noticing crucial details and significant patterns — as does radiology. In addition, “photography strengthens my ability to do away with distracting ‘noise’ and focus on the task at hand,” she says.

Meltzer notes another benefit of photographing nature: It helps hone the patience she needs as a leader. “When I’m taking a photo, I may need to wait an hour until the light is right. When I’m having conversations with people, I need to give them the time they need to feel heard,” she says.

Photography — and other artistic pursuits — can also help medical providers cope in uncertain times, Meltzer believes.

“Lately we seem to wake up to a new surprise every day, which can make us quite anxious, so I’ve committed to making sure to take the time to do what I enjoy,” she says. “I know I need to take care of myself so I can be there for everyone else.”

The healing power of poetry: A writer-rheumatologist

Poetry sustained Leena Danawala, MD, during one of the toughest times in her life.

At 21, with half of her training at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine still ahead, Danawala developed symptoms — joint pain, neuropathy, vision problems — that drove her to take what she believed would be a short leave.

Two years later she was finally diagnosed with the rare disease granulomatosis with polyangiitis, an inflammatory condition that restricts the flow of blood throughout her body.

“During my leave, I went to the library three to five days a week and wrote or read poetry,” says Danawala, now a rheumatologist at Advocate Health Care in Park Ridge, Illinois. “Taking time off, I lost my sense of direction. Poetry helped steer me back to what was important to me, including finishing medical school,” she adds.

Writing poetry continues to be crucial in helping Danawala handle the challenges that come with her condition, which involves receiving care from five to seven doctors.

“Writing helps me clarify and process my emotions. Sometimes, I don’t even realize I feel a certain way until I start writing," she says.

Among those feelings has been a stark sense of loneliness. “It’s hard for people to understand what my life is like,” she says. “Taking care of myself is like a second job, and I can’t just make spontaneous plans with people.”

“Poetry helps me connect with others, even if I don’t know who’s reading what I write. It helps me feel heard,” Danawala says. Although her poems have been published in JAMA Poetry and Medicine, she’s happy just to post them on her Instagram page.

Danawala also experienced grief at losing the person she’d been before becoming ill. “I had been very athletic and social, so I lost part of my identity. Through poetry, I saw what role I wanted to play in the world,” including helping patients who have conditions similar to hers.

Danawala adds that processing her emotions through poetry makes her more emotionally available to patients, which she considers a crucial part of care.

“Patients want to feel heard,” she says. “If doctors don’t build connections with them, patients are much less likely to trust us, and they are much less likely to follow our advice.”

rest, like a river

I like the idea of a river yawning:

its mouth a vast open width,

just a symptom of fatigue.

I think of how it wraps its length

around itself, serpentine and sure;

how its waves rock back and forth,

a cradle on an unsteady floor.

on days like today, when the

spring fog has melted into my bones,

or when time seems to stop or slow,

I think of my spine as that river

and curl into myself like the letter “c.”

breath floating downstream,

body swaying like the currents of the sea.

– Published in JAMA Poetry and Medicine, December 2024

Giving voice to patients and himself: A singing otolaryngologist

Chris Puchi, MD — whose videos have garnered millions of TikTok views — chose the field of otolaryngology for many of the same reasons he sings.

“As a singer, a key focus is on communicating, and otolaryngology is all about communication,” says Puchi, a fifth-year resident at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “If I can help a person hear, they can better engage with the world, and if I can help someone speak, I am literally helping to give them a voice.”

Music has been central to Puchi since his days growing up in Venezuela — his family left when he was 9 years old — where his father was a well-known musician. “Latin music has had a big influence on me. It’s surprisingly broad, so I’m comfortable with many different styles,” says Puchi.

That might be something of an understatement.

Puchi belts out show tunes such as Wicked’s “Defying Gravity,” croons Disney ballads like “A Whole New World,” and delivers renditions of Pearl Jam, Foo Fighters, and Bruno Mars with equal ease. In addition, he starred in musical theater during college and has since performed as a solo artist as well as in choirs at numerous venues. Among those are several medical conferences, including Learn Serve Lead 2024: The AAMC Annual Meeting, where he sang The Fray’s How to Save a Life.

Music has certainly served him as a physician, says Puchi, partly as an outlet for decompressing but as a way to sharpen teamwork skills too. “Medicine is a bit like being in a choir. You have to do your own part, but you also have to adapt to those around you.”

What’s more, music can help build bridges, he says.

“I can join a band with anyone from any background, any culture, or any political belief, and anyone from any background can enjoy it,” says Puchi. “In these times of division, music can create beauty and help unite people.”

The body as a work of art: An illustrator-surgeon

Stephanie Cohen, MD, knew she wanted to be a doctor from the time she was young.

“My mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when I was a child, and I was frustrated watching her body work against her. Wanting to fix her ailments and those of others drew me to medicine,” says Cohen, a surgical resident at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

But Cohen also knew she had to create art.

“I’ve been drawing almost my entire life. I tried to give it up in high school, and it didn’t go well,” she says. “I felt like part of me was missing.”

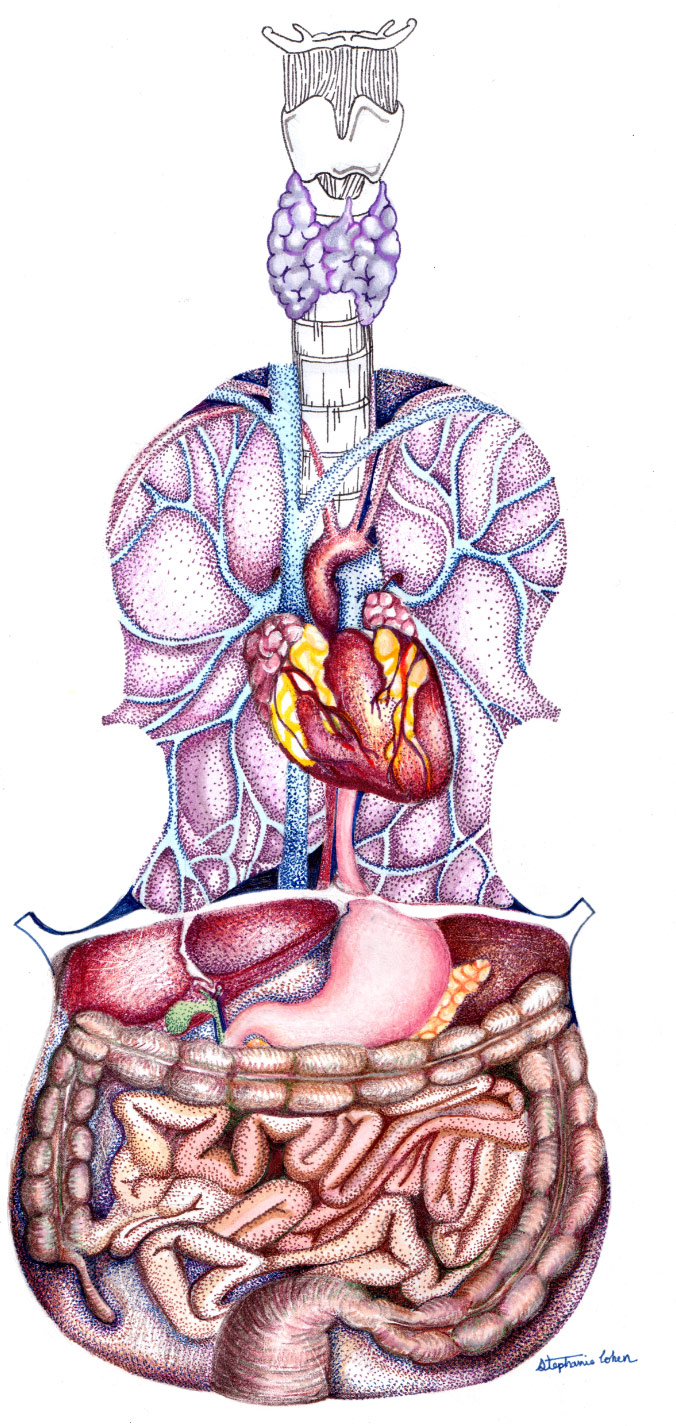

Now 30, Cohen has figured out how to do both in her careers as a surgeon, creative artist, and medical-textbook illustrator.

Cohen’s more playful works — mostly ink drawings — capture her abiding appreciation of the human form. “I see human anatomy as a work of art. It’s incredible the way our organs work together to allow us to function,” she says.

In one image, Cohen depicts lung branches by drawing graceful tree limbs. In another, she portrays the heart as a cabbage — a pun on CABG, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

In addition, Cohen’s artwork often highlights the connection between human physiology and the world of music. In one piece, Cohen — whose musical parents signed her up for violin and piano lessons at age 4 — seamlessly merges saxophone key pads with spinal vertebrae.

“I first noticed the similarities between music and anatomy when I learned about the pathophysiology of cancer. In cancer, cells become unresponsive to their environment and divide out of control. I imagined a rogue instrument ignoring the conductor, leading to musical dissonance,” she says. “In both cases, a small event affects the entire system.”

Cohen believes it’s crucial to teach future physicians the connections between art and medicine.

In the fall, she’ll co-teach a medical-illustration course at a national surgical conference, and she helped launch a curriculum for surgical residents designed to improve their communication and observational skills. “The beginning of a physical diagnosis is all about intentional and careful looking,” she says.

Cohen also sees art as a crucial outlet for reducing stress.

“Every decision we make in medicine has implications for patients and their loved ones. In art, even when things don’t turn out the way we want, no harm is done,” she says.

“We all need a way to pay attention to the small joys of life and to connect with others. Art can provide that.”

The serious side of cartoons: A medical-educator and New Yorker cartoonist

Benjamin Schwartz, MD, is convinced that drawing cartoons helps turn medical students into better doctors.

That’s why each year, Schwartz — a New Yorker cartoonist since 2011 — teaches several courses at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons that get students to sketch and scribble.

“I know it’s a bit weird,” admits Schwartz, a Columbia assistant professor. “I acknowledge that it’s very strange that they’ll spend the next few weeks drawing cartoons.”

“But there’s a logic to it,” he adds.

For one, drawing fosters communication skills. “It gets you to focus on what your audience is thinking, what they need to know, and how they might react,” he says.

Comics also make an excellent medium for conveying tough information to patients, Schwartz believes. “People associate cartoons with play and childhood, which can make difficult topics like illness much less scary,” he says.

Beyond getting students to draw, Schwartz has created cartoons to teach them medical content. “Medical textbooks usually inset images, which means you have to stop reading and shift over to the illustration,” he says. “But in a comic, the visuals and text are integrated, which makes it easier to process information.”

Although Schwartz no longer provides direct patient care, he uses his artistic vision to advance patient education. In fact, it’s won him an unusual role — chief creative officer in the department of surgery — in which he oversees the creation of web, print, and social media content.

Being able to pursue his artistic side “has meant everything to me,” says Schwartz. “I can’t believe how fortunate I am that I get to be in both medicine and the arts.”

Editor’s note: The AAMC has a long-standing initiative to support the integration of the arts and humanities in medical education. Find resources for medical educators and learn more about the Fundamental Role of Arts and Humanities in Medical Education (FRAHME) initiative.